Bloomberg -Dina Bass

- They stress customization—and the fact that they don’t compete with clients.

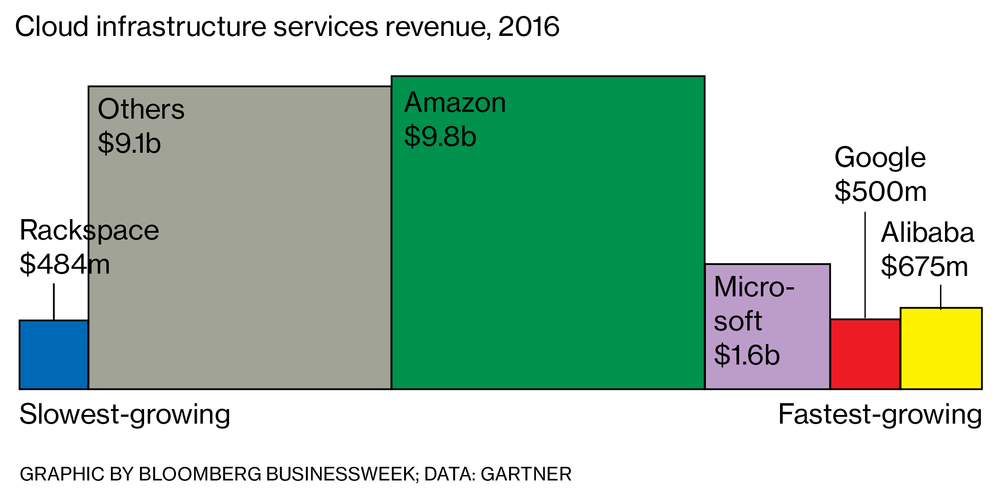

It’s hard to think of a business Amazon.com Inc. dominates as convincingly as the market for cloud computing services. Andy Jassy, chief executive officer of the company’s cloud division, Amazon Web Services Inc., likes to brag that his outfit has several times as much business as the next 14 providers combined. Amazon’s next-largest cloud competitor, Microsoft Corp., is less than one-fifth Amazon’s size in terms of sales of infrastructure services, which store and run data and applications in the cloud, according to research firm Gartner Inc. Google, the No. 3 U.S. cloud services provider and the second-largest company in the world by market value, makes one-fifteenth of Amazon’s cloud revenue.

“AWS effectively defined the notion of cloud computing,” says Gartner analyst Ed Anderson. “It’s perceived as the cloud leader and pacesetter.” AWS generated $4.6 billion in sales in the most recent quarter. Every year, it introduces dozens of features and products to retain its edge.

“Microsoft is at the leading edge of today’s game-changing cloud-based technologies,” CEO Satya Nadella wrote in his autobiography, published in late September. “But just a few years ago that outcome seemed very doubtful.” As part of Nadella’s catch-up strategy, Microsoft has transformed its sales force into a roving R&D lab and management consultancy. Startups get introductions to potential investors and prospective partners and customers. Big companies get access to a sales team that helps market the cloud apps they build on Azure to their own customers so they can make a buck on the software they use in-house.

The sales team includes 3,000 dedicated software engineers who can build applications for prospective clients during sales calls, demonstrating on the spot what they can do for them. “I can’t send people to a customer anymore to give a PowerPoint presentation,” says Judson Althoff, executive vice president for Microsoft’s worldwide commercial business. Once a customer signs on, Microsoft engineers can be deployed to the client the next day.

Bill Braun, Chevron’s chief information officer, says Microsoft impressed him by showing off machine learning software that will allow his company to analyze volumes of data from oil production equipment to detect tiny changes in temperature or vibration, early signs of faulty equipment, or other problems. “They understand the enterprise,” he says.

Microsoft’s sales team made the pitch with the help of HoloLens, the company’s new augmented-reality headset. When paired with Microsoft’s cloud software, the headset allows Chevron’s senior engineers to virtually oversee the work of software technicians around the globe as they install equipment.

For years, Microsoft representatives have sold the company’s signature Windows and Office software that clients install on their computer networks. More recently, they’ve moved some of those clients to Office apps in the cloud. Clients accustomed to those cloud applications may be more likely to go with Microsoft when they decide to replace their own data centers and servers with public cloud infrastructure, says Gartner’s Anderson.

An existing relationship was why candymaker Mars Inc. chose Microsoft instead of AWS last year. “Our philosophy is to drive deeper relationships with partners we already have,” says Paul L’Estrange, Mars’s chief technology officer. “We didn’t have that same sort of relationship with AWS.” Google is trying to set itself apart with TensorFlow, software that makes it easier to build artificial intelligence apps, and with Kubernetes, a software system which helps companies better manage their data in the cloud.

Even Google, a company that has been generally allergic to using people for anything a machine can do, has seen the value of having a human sales force. In late 2015 it hired corporate software veteran Diane Greene, a Google board member and co-founder of VMware Inc., Dell Computer’s cloud computing subsidiary, to run its cloud business. She’s been building a cloud sales force from scratch. Google recently announced a partnership with Salesforce.com Inc. to take advantage of the latter’s list of preferred cloud providers.

Both Google and Microsoft have sought to exploit another of Amazon’s perceived weaknesses: that other parts of its empire compete bitterly with prospective cloud customers. Amazon’s retail rivals, including Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and Bangalore-based Flipkart Ltd., don’t want to see their Amazon cloud payments lining the coffers of the retailer that could ultimately put them out of business, says Gartner’s Anderson. Flipkart signed up with Microsoft in February. According to a June report in the Wall Street Journal, Wal-Mart has been telling its tech suppliers not to use AWS. Wal-Mart didn’t respond to a request for comment. CEO Jassy says AWS treats all its cloud customers, including many Amazon retail rivals, equally.

After several years on AWS, Lush Ltd., the U.K.-based toiletries company, jumped to Google Cloud in November 2016. Lush has sued Amazon, claiming the company is using Lush’s trademarks to sell rival bath goods.

“We’re not particularly keen on Amazon as a company, so we’d prefer not to work with them,” says Jack Constantine, Lush’s chief digital officer. Amazon declined to comment on the lawsuit.

“It’s not a surprise to us that every large tech company in the world is interested in building a replica of what AWS has done,” says Jassy. Whether or not it’s feeling the pressure, the company is spending more time cultivating relationships with top executives and CIOs. It’s hosting dinners with prospective clients to address their concerns in more intimate settings and bringing more of a human touch to these relationships. “They’re making themselves accessible,” saysAdam Johnson, CEO of IOpipe, which provides monitoring and troubleshooting services to businesses running on AWS.

Its reputation as the market leader means those executives and chief technologists tend to lean toward AWS when all else is equal. Its early lead—AWS beat Microsoft to the market by four years—gives the company an automatic edge. And Amazon’s cloud services are seen as the safe bet, no small thing in an age of hacks and denial-of-service attacks. Sometimes even when a company thinks it can claim a win over AWS, it can’t broadcast the victory. In March, Google published a blog post announcing that Airbnb Inc., a longtime AWS client, had agreed to use a Google cloud service for AI. The following day, Airbnb’s name was scrubbed from the post. Airbnb and Google declined to comment.

So for the near future, at least, AWS looks like it will continue to rule a market that Gartner expects to generate $89 billion in sales by 2021, up from $35 billion today. “There’s a humongous amount of growth in front of us,” Jassy says. “This is the biggest technology shift of our lifetimes.” —With Spencer Soper and Mark Bergen